India’s troubled history of vaccination

On June 14, 1802, three-year-old Anna Dusthall became the first child in India to successfully receive the smallpox vaccine. Only the barest details are known about Dusthall— she was a healthy girl, possibly of mixed racial identity, “remarkably good tempered” — a trait crucial to the vaccination’s success — and, from the pus that formed on her skin upon vaccination, five more children were vaccinated in the city of Bombay. Thereon, enough vaccine material was collected using her lymph and sent to Poona, Surat, Hyderabad, Ceylon, Madras and more places along the coast and the Deccan.

Dr Helenus Scott, the physician who vaccinated her, hoped that with the availability of the vaccine, “one of the greatest evils that has afflicted humanity” would be diminished or even extinguished. His wish would take root, but not before a confusing century, riddled with challenges and challengers, passed by. As recent research indicates, the history of smallpox vaccination in colonial India wasn’t a simplistic colony-versus-empire dynamic. British and Indian officials would have to contend with diverse fluctuating reasons for the public’s unwillingness to get vaccinated, each concern specific to different sections of society. The opposition, while not widespread, was nearly at every step — right from the vaccine’s safety to its disregard for local cultural and medical practices — and if officials felt they could bulldoze their way through, that was hardly the case.

If there is one feature that marks the periods and contexts of smallpox and COVID-19, it is the issue of trust, observes Sanjoy Bhattacharya, professor, University of York, the UK, who heads the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Global Health Histories. While a safe vaccine and vaccinating practices were crucial to creating basic confidence, other factors — such as planning, the willingness of culturally important figures publicly accepting vaccination and the hands that transmitted the vaccine to disparate and complex social groups — were as significant. “A single political event, which annoyed the British Indians, like the Rowlatt Satyagraha (1919), could suddenly increase opposition to all visible forms of state intervention, like smallpox vaccination,” he says.

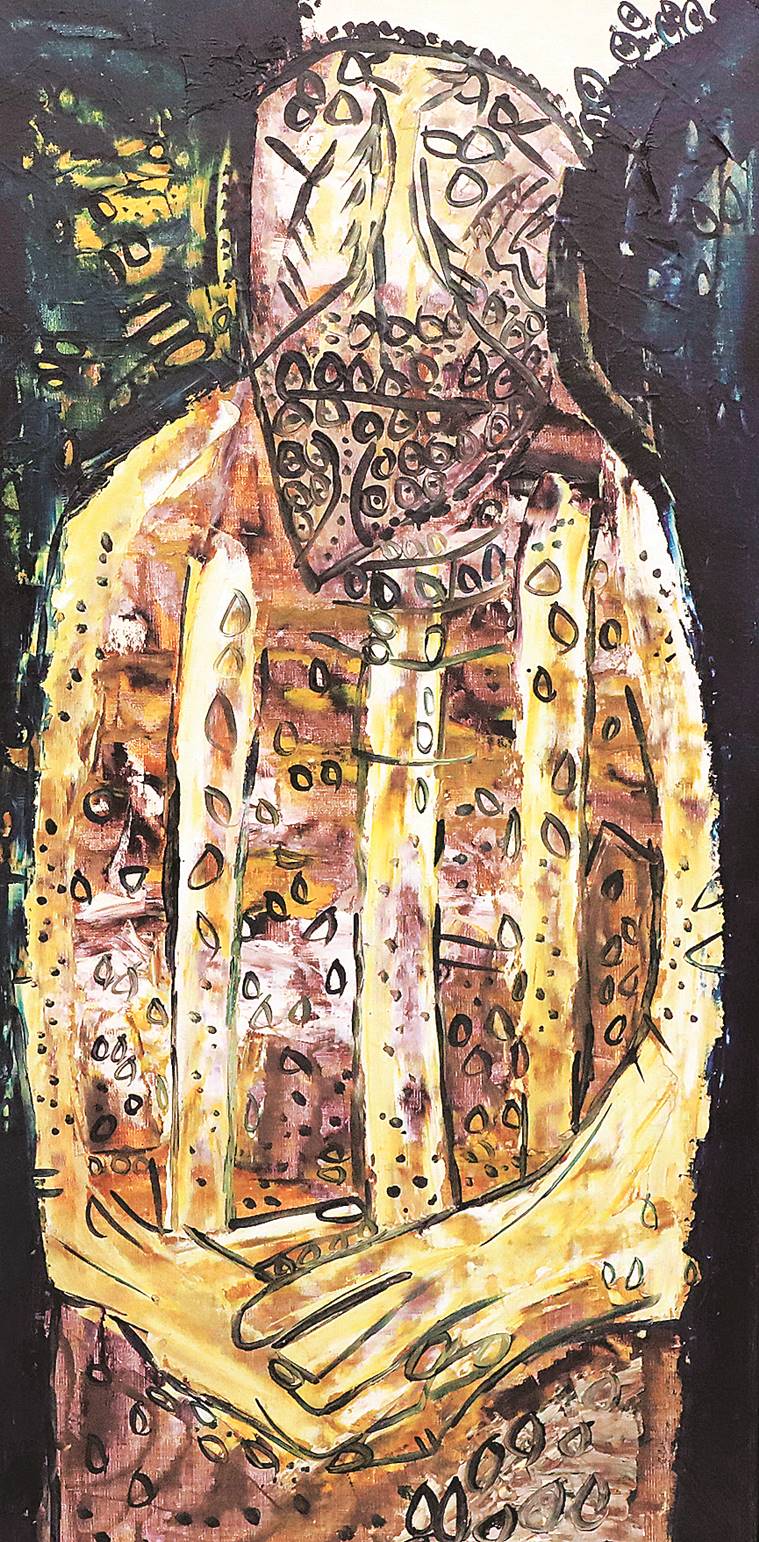

Unlike COVID-19, a disease that we are still learning about, smallpox was well charted and notorious, dreaded both in India and Europe. Those who survived were left horribly disfigured and blind, and often had a hard time reconciling with the aftermath. Queen Elizabeth I painted her face lead white and 18th century European aristocrats often wore beauty patches — fabric stickers shaped like hearts, moons and stars — to hide their pockmarks. Even in the 20th century, renowned Indian Modernist FN Souza would paint grotesque, pockmarked figures after his own recovery from smallpox as an infant. “Stars in the face are the scars of smallpox,” he would write.

Smallpox was endemic through the Indian subcontinent, turning into an epidemic every five years or so. Around the time of Dusthall’s vaccination, it was estimated that smallpox mortality in India was one in three cases. It’s hardly surprising therefore, that Dusthall’s vaccination was a cause for imperial optimism. The vaccine, introduced by country doctor Edward Jenner, used cowpox to produce immunity against smallpox (the word “vaccine” comes from the Latin vacca for cow and vaccinia for cowpox). By 1800, Jenner’s vaccine was delivered “arm-to-arm”, where lymph was taken from vaccine incisions and administered to other subjects.

India’s first vaccination was a concentrated effort across continents. In 1799, Jenner sent threads soaked in lymph vaccine to Vienna; from Vienna via Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) and then to Baghdad. A vaccinated child from Baghdad was sent to Bussorah (modern-day Basra), and from the child’s arm, successful vaccinations were performed. More lymph was raised here, and, finally, in May 1802, a batch was dispatched to Bombay, where Dusthall was one among 20-odd children to receive it, but the only successful outcome. This intercontinental relay was often lauded in official accounts, but the British administration was yet to fully comprehend the problem of lymph logistics.

In 1805, John Shoolbred, the superintendent general of vaccine inoculation, stated they were keen that Bengal’s provinces received the vaccine. But “the whole tribe of Brahmin inoculators” were determined enemies of the new practice, Shoolbred noted, and were using their influence to stop parents from presenting their children for vaccination.

The tikadar or inoculator/variolator was a product of the region’s existing method of developing immunity against smallpox. Tikadars would manually induce smallpox with preserved dried scabs from previously inoculated subjects. A 1767 account describes how scabs were first sanctified in the water of the Ganga and subjects prepared for inoculation by abstaining from fish, milk and ghee.

The system wasn’t without its flaws — so long as the smallpox virus was present, the risk of outbreaks existed. To quell the tikadars’ influence, in 1805, pensions were granted to those willing to relinquish their practice in and around Calcutta. Some 50 years later, variolation was equated to outdated practices such as sati and infanticide. Acting as both doctor and priest, tikadars were called the ministers of Sitala, the goddess of smallpox, who was supposedly angered by vaccinations.

The administration wasn’t always wholly opposed to variolation. The practice was prevalent in Britain as well, until it was outlawed in 1840. Bhattacharya says that official smallpox control measures — first through variolation and later through vaccination — remained an important facet of British colonial administration in the 19th and 20th centuries. When vaccination first arrived, it was hardly the reliable and safe technology it was made out to be. It is only when British-Indian vaccination technologies and working practices became more reliable, that official support for the new intervention increased. “It was all a question of relative risk,” he observes. Variolation was considered safer than smallpox; vaccination, when it could guarantee protection, was better than variolation.

Weeping mothers, angry fathers and parents absconding with their children before or after vaccinations are common tropes in many official accounts from 19th century India. Indeed, the figure of the vaccinator, who was always Indian, often assumed terrifying proportions. “In these days, vaccinators are a source of annoyance and oppression to the subject population,” noted the newspaper Sindh Sudar (November 26, 1887). The complaint was regarding an incident at a fair, when a vaccinator caught hold of a boatman and his infant, took matter from the child’s incisions and blindly used it to vaccinate every child he saw. Thousands at the fair ran away seeing him. Similar accusations erupted across different parts of British India in the 19th and 20th centuries. The details are different, but the storyline is nearly the same — the public as prey, the vaccinator as predator.

“Even today, people are afraid of injections. You tell them it’s just a prick but it doesn’t stop their fear. It’s just human behaviours and fears which come in to play,” says epidemiologist Dr Chandrakant Lahariya, co-author of the book Till We Win: India’s Fight Against the COVID-19 Pandemic (2020). For most of the 19th century, vaccination was not a quick jab but implemented by a variety of lancets. With the arm-to-arm method, children not only had to bear with the painful procedure but also the extraction of lymph for further vaccinations. Lahariya adds that the acceptance of a vaccine has always been on a spectrum, with those who will take any vaccine offered and those who will refuse every vaccine, no matter how much the scientific evidence, at either end. “There has never been a period when opposition to a vaccine wasn’t there,” he observes.

Namrata Ganneri, assistant professor, history, SNDT College of Arts and SCB College of Commerce and Science for Women, Mumbai, notes, “One of the most important reasons for opposition has always been a doubt in the efficacy of the vaccine.” The liquid lymph, used till the 1950s against smallpox, lost potency in warm temperatures and, in the absence of adequate facilities of refrigeration, the vaccine remained ineffective.

One of the chief debates surrounding COVID-19 vaccinations is about whether to make jabs mandatory, in the interest of public health. Concerns around smallpox vaccination were no different in colonial India. Right from the beginning of the vaccination efforts in India, there were suggestions in the press that a persuasive rather than coercive effort would do the trick. There were others who believed that force would be the best way to promote the vaccine. Compulsory vaccination acts were passed in different parts of the country from the late 1870s onwards, with imprisonment or fines as penalties for evasion.

In 1898, Great Britain banned arm-to-arm vaccinations, citing that syphilis and hepatitis spread through the practice. Calf lymph was seen as a safer alternative. Bovine lymph production took off in India in the late 1800s and vaccine research and production depots were set up. Calf lymph was welcome as caste and religion had undoubtedly been a concern with the arm-to-arm method. “High” caste Indians believed it would be ritually polluting to be vaccinated with the lymph of “lower” caste children. Influential members in the Bombay Presidency argued that a wise government wouldn’t overlook caste and religion, despite what reformers had to say.

Indeed, officials had previously tried to categorise how different castes and religious groups reacted to vaccination efforts. Some vaccination reports of the Bombay Presidency and Sind (1872-73 and 1874-75) lamented that the vaccine department had no influence whatsoever on “the Mahomedan portion of the community, from the poorest mendicant and fakir to the richest merchant and millionaire…” in Bombay. Overall, in 1874-75, Muslims were seen as accepting the vaccine more freely than Hindus, except in the Bombay circle, where they were perhaps too careless or too busy to give thought to a probable danger. The Kolis were criticised for their belief in a Devi who would rather claim her victims sick than vaccinated. Parsis didn’t fare too elegantly in the eyes of this report either. The community “out-hindued the Hindus…in their superstitious regard for smallpox”. There was a good deal of opposition to the vaccine among the native Christians of Salsette; some native Christians in Kurla were open to their children being vaccinated but opposed lymph extraction for further vaccinations.

If officials believed that the public would wholeheartedly embrace vaccines developed from a creature revered by many Hindus, then they were served a lesson in nuance. In 1913, Mahatma Gandhi stated, “vaccination seems to be a savage custom…Vaccine from an infected cow is introduced into our bodies…I personally feel that in taking this vaccine we are guilty of a sacrilege.” In 1929, he would go on to remark that vaccination was “tantamount to partaking of beef”.

Niels Brimnes, associate professor of history at Aarhus University, Denmark, takes into account these and later statements by Gandhi in an essay published in 2017. He explains that there were a number of reasons among the rural masses for following Gandhi but scepticism to vaccination was not among the main ones. He says, “Opposition to Western medicine, including vaccination, was important to the articulate sections of the nationalist movement, because it allowed it to construct a national identity that took pride in the alleged achievements of Ayurvedic and Unani traditions. Medicine became an area where the nationalist movement could claim that India had a distinct and valuable scientific tradition of its own.” The “nationalist” position on medicine was forcefully countered by modernist forces immediately after independence, such as by Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, Union minister of health for a decade after 1947, who was strongly pro-western medicine, and would never question the value of vaccinations.

Brimnes observes that if local leaders in a village supported smallpox vaccination, many villagers would likely follow their lead. “It is not much different from today, where doctors and politicians might be asked to undergo vaccination publicly to persuade people to accept a vaccine,” he says.

Similarly, in Bombay, portrayed as one of the best examples of successful vaccination efforts, the role played by Indian doctors was vital in establishing trust. Historian Mridula Ramanna notes that in the 1850s, the British government established vaccination depots in several parts of the city, with the support of the first batch of students who graduated from Grant Medical College in 1851 to promote smallpox vaccination among Indians. Among them was Dr Bhau Daji, after whom the city’s museum in Byculla is named. He had a charitable dispensary at Nagdevi Street, from where he was able to recommend the vaccine to patients who sought him out every week.

In 1980, the WHO declared, “Smallpox is dead”. The last case on the Indian subcontinent would be three-year-old Rahima Banu Begum in 1975, who was treated and her scabs sent for further study. From Anna to Rahima, the scourge was eradicated, but leaving us with important lessons on continually checking the temperature of cautious and complex groups of people, for whom “one nation, one rule” may not suffice.

Marks of mortality: FN Souza’s oil on canvas Untitled (Pope), 1961; Souza often painted pockmarked figures after his own recovery from smallpox as an infant (Source: prinseps.com)

Marks of mortality: FN Souza’s oil on canvas Untitled (Pope), 1961; Souza often painted pockmarked figures after his own recovery from smallpox as an infant (Source: prinseps.com)